Meanwhile, back at Gallaudet...

Vox and Curbed produced this clip that highlights a lot of the work we did at Gallaudet back when we were working at Studio 27 Architecture.

The building formerly known as The Snail. ©Alice Hoachlander

LEED Platinum snail

The Mundo Verde Bilingual Public Charter School was one of the last projects we worked on at Studio 27 Architecture before heading out on our own. The project comprised a renovation of a 1920's brick school building, and the construction of a new, free-standing annex for the youngest students. Around the studio, the annex was known as the "Kinderhaus", owing to Hans getting his hands on it first. Fortunately Hans is fluent in Spanish as well as German (and French and some other stuff...) and Mundo Verde is very clearly a bilingual Spanish/English language school. So the Kinderhaus became the Casa Caracol (the Snail House), in reference to an early design that had a sloping, wrapped circulation path. Later, as the process to make LEED Platinum slowed the project, snail house took on a different meaning. The project just won an AIA Committee on Architecture in Education design award. Thanks to John and Todd at S27 for giving us the opportunity to help realize this unique project.

Under the stairs

Our Capitol Hill townhouse project is undergoing demolition, and history is falling out of the walls along with the dust. Among the artifacts, a high school yearbook and photo album from the 1940s. Our client is trying to track down the original owner of the books. Other things revealed: layers of construction techniques: sheetrock over older sheetrock, over plaster over lathe over brick...

Raise/Raze = Demo-cracy/lition

The Re-Ball! design competition winning installation Raise/Raze has opened to the public, and sold out its month-long run in 24 hours. You can take yourself on a 3D walk-through of the installation here. While Archotus is busy directing the exhibition, above is a time-lapse of the "sand-box", the area where the public can create and destroy the installation. This creative destruction dynamic is worthy of a deeper blog-post, but in the meantime below is some of the press we've received thus far...

“Underneath Dupont Circle: a playground for democracy” – Washington Post

Raise/Raze opening in the media: CBS, ABC, Washington Post…

Dupont Underground on the Kojo Nnamdi blog.

If you need it built, they will come.

Some lessons about crowdsourcing your buildout

Project managing an art installation like Raise/Raze requires wearing multiple hats. There is the Studio Critic hat - teaching each new wave of volunteers how to make the thousands of cubes we need to build the installation, and doling out some tough love when they do it wrong. There is the Cheer Leader hat - keeping everyone focused and enthusiastic despite working in a cold underground space with bad light and no bathrooms. Then there are all the ancillary hats required to get the space ready. These include, but are not limited to: electrician, lighting designer, carpenter, engineer, pest "management" (sorry rats), it goes on.

One thing is clear, expecting a random assortment of volunteers to have the skills required to make art, however simple and straightforward, was a bit naive. In the early days, we created a series of jigs to expedite the process. But after the first week of volunteer production (25-30 volunteers a shift for 2x2hour shifts on weekdays + 4x2 hour shifts on weekends = 400-500 people per week...each needing to be taught anew) we realized we needed something on the order of Ikea assembly instructions, in audition to our own verbal explanations. Josh and Nancy created the requisite documents:

Here are the jigs in action:

And still, there were lots of rejects....

Going into the final week, though, we are pushing 12,000 cubes, and we are Raising Raise/Raze!...

last two photos courtesy BYT (thanks guys!)

This is what we need to build.

In Which We Give Citylab a Preview of Raise/Raze...

Dupont Underground is officially a thing. Archotus spent much of 2015 consulting with the Washington DC arts non-profit to develop a curatorial plan, in part to stir fundraising and municipal and community support, but also to have the opportunity to do something really cool. That cool thing became Re-Ball!, a design competition asking entrants to repurpose the 750,000 ball-pit balls from the National Building Museum's Beach exhibit and create a unique installation within the Dupont Underground.

The Re-Ball! competition had over 150 entrants from 19 different countries. Archotus assembled an awesome jury, and five finalists were chosen. Hou de Sousa's Raise/Raze was the winner, and now the hard work begins. Archotus will spend the next six weeks wrangling volunteer installation assemblers and building a massive reconfigurable environment. Hou de Sousa projects we will need about 3000 work hours just to build the components, let alone the environment. Archotus will be directing the effort and the build out. Citylab's Kriston Capps understands what this is going to take...

streetcar of the dystopian future?

iGlow Worm

iGlow is a thirty-six-foot-long glowing lavender tunnel composed of faceted surfaces perforated by parametrically warped holes. Visitors walking in the tunnel appear, from the outside, to be warped into pixels as they pass through. Analog bodies in motion project digitized images through the tunnel surface via a combination of light, distance, and surface-to-void repetition.

iGlow is the brainchild of Hiroshi Jacobs, founder of HiJac, a Washington DC-based design collaborative. It originally appeared in Georgetown Glow -Washington’s answer to Festivals of Light more common to European cities like Florence, or Lyon. Georgetown Glow lasted one week, and iGlow was destined for the recycle bin.

...light, tunnel, action.

We’re not sure who had the idea first but simultaneous light bulbs went off at HiJac and Dupont Underground: IGlow belonged deep in the hidden tunnels of the Underground. This past weekend we made it so. An intrepid group of ten assemblers, led by Hiroshi, dragged the disassembled iGlow to the southern terminus of Dupont Underground -1000 feet from the nearest entrance - and rebuilt it in the darkness of the abandoned streetcar tunnel. Here it took on an entirely new character; perhaps a technological worm, or the train from the Wong Kar-wai movie 2046, zooming through a post-apocalyptic Hong Kong. The segmented structure of the streetcar tunnel surrounding the segmented structure of iGlow complement and heighten the effect of each, throwing light and shadow in an entirely new way.

if you build it they won't come. but that's okay.

Unfortunately this installation will not be seen by the public any time soon, it is too deep and remote to access. Special guests to the Dupont Underground, after signing waivers, can go on small group tours, but the installation will remain an insider exclusive until Dupont Underground finds enough funding to make its deepest tunnels publicly accessible, which will take many years. In the meantime, we have some pictures…

Arno Brandlhuber knows how we live and work...

Meanwhile at the Archotus office: one room, endless possibilities

This interview over at freundevonfreunden with Berlin-based architect Arno Brandlhuber touched a nerve today...

"I don’t need more than one room. I’m either in bed or in the bathroom, in the kitchen. I’m either reading or working. Since I can only be in one place at a time, it’s enough if this one place provides for all functions equally. For this reason there are no walls here, only around the bathroom. I think that we are much too stuck in the belief that our living spaces have to resemble those of our parents – even if we thought we had detached from them after a few tough processes..."

Reality Check

Triennales ask the darnedest questions. While brainstorming ideas for the call for entries for next year’s Oslo Triennale I fell down a rabbit-hole of disciplinary self-loathing. As of yesterday, after the third false start, I have abandoned trying to enter this competition. It happened like this.

First, the backgrounder: The theme of the 2016 Oslo Triennale is “After Belonging”. It asks entrants to respond to various ways our sense of belonging - how we belong, what we belong to, and what belongs to us - is changing as we humans are more and more in a state of transit, physically, psychologically, and virtually.

The design portion of the call for entries gives five sites for interventions, and four of those sites are either implicitly or explicitly implicated in the refugee crisis unfolding in Europe. The sites are: A refugee asylum center in a suburb of Oslo; a mid-century modern housing project that is now mostly occupied by migrants and refugees in a suburb of Stockholm; a town on the Norwegian/Russian border in the Barents zone where Syrian and Afghan refugees have discovered a back door into Europe; and the zone of transfer - the border zone, so to speak- at the Oslo international airport. The fifth site (the one not implicated - for now - in Europe’s refugee crisis) is a hypothetical typical Air BnB apartment.

So, given that a major crisis is unfolding that impacts each of these sites how the hell does one propose an architectural intervention that is relevant? With facts on the ground changing daily - Paris terror; a real possibility of losing Schengen - many ideas that might seem worthy in 2015 might very well be moot, or just silly, in 2016.

My latest -aborted- concept accepts the that the situation at the moment is beyond architecture, and that in order for design thinking to have a place in approaching quickly-evolving problems you need to go extra-disciplinary. I came up with an idea involving more of an event than a material solution, and made a list of people I knew whose work or life experiences give them far more direct access to the problems and people I was proposing to address. Then I started getting in touch.

And…was stopped short by the first person I reached out to.

This first contact was a journalist friend of a friend who had an extended, horrific, life-changing experience in Syria from which it is a miracle he returned alive. I won’t name him because he is rather famous and would probably not wish to be implicated in this. I sent him a draft of my concept - admittedly written as if I was proposing it to a bunch of architecture PhDs (read: obtuse and jargon laden). He answered quickly:

“My feeling is that you wouldn’t want to oblige—or even ask—any refugee from anywhere to [do this thing I was proposing]. I spent this morning pulling refugees from ocean here on island of Lesbos. The people are not exactly in the mood for [doing this thing I was proposing]. They need a million things. [This thing I was proposing] is not one of them. By giving them [this thing I was proposing], I think you’d look foolish.”

He closed by giving a less-than gentle jab at my architect-prose: “Also, the “extra-disciplinary provocation”—I don’t know what that is but it doesn’t sound like anything I would wanna be involved in.”

Now, in all honesty, what I was proposing, was - in the larger ecology of speculative architectural proposals out there in the world - actually fairly humble. Something in the spirit of this, except involving bicycles and a bit of a trip. I am not revealing it here because (a): I’m still too embarrassed, and (b): in the back of my mind, wherein lies my ego, I still think it is not a completely bad idea - given another population. Nonetheless, this experience led me think about the longstanding disconnect between architects and the world as lived. Here I was, caught in my own competing ambitions. On the one hand I wanted to do something that would have a positive impact on a tiny snippet of the refugee crisis, but that would also scratch the creative itch in such a way that would bring praise and notoriety from my field. In reaching out to someone outside of architecture, who has no knowledge of its direction and discourses, I was reminded of how we architects often appear to the rest of the world: out of touch and self-absorbed.

This smarts. In part because in architecture there is an over-played schism between the social actors and the formal actors. It is the latest version of form vs. function, wherein the formalists criticize the trend in architecture to overvalue design for social change, and the formalists are criticized for folding architecture into itself and focusing only on novelty, parametricism, and affect. The formalist criticism of the social actors is run to ground perfectly in the situation I found myself facing with the Oslo Triennale: give it up, man, you have to step out of architecture to truly accomplish anything social.

I don’t want to believe this, but time is up and I’ve run out of runway to launch a plane full of happy solutions to the worlds problems. Bon voyage to all my colleagues who will thread this needle to varying degrees of success; I can’t wait to see what awaits in Oslo.

The four situations entrants in the Oslo Trienalle will have to either embrace or politely step around:

Bicycle-born refugees in Kirkenes, Norway.

Growing migrant and “Nativist” stress in Sweden.

Overwhelmed asylum centers.

Over-burdened “Have and Have Not” (in this case - a passport), architectures of the Oslo International Airport.

Sous les pavés...

Last week, we moved the balls from the National Building Museum's "Beach" exhibit here...

I'm sure the Illuminati have a name for this shape, but no one knows what it is...

Dupont Underground is an empty space (now inhabited by 750,000 plastic balls) and an idea. It is 75,000 square feet of disused streetcar tunnels and platforms extending 10 city blocks under Dupont Circle and its commercial corridor along Connecticut Avenue in Washington DC. An organization was formed in the early Oughts to reactivate the tunnels. With only volunteers, and a negligible budget, they were able to convince the city to grant them a five year lease on the tunnels in late 2014.

tunnels...lots of 'em

Within the Dupont Underground organization, there have been wildly varying ideas of how the space can best be used, but the clearest most consistent concept has been as an alternative space for contemporary arts. Washington has many venues for arts, but they tend to be conservative. Washington DC, for all its importance as a world capital, has a culture gap. The District is not known as a place that generates new thinking in art, architecture, or design. Nor is it considered a receptive destination for art that challenges the status quo.

courtesy Josh Kramer comics, Washington City Paper

Since Spring of 2015, Archotus has been advising Dupont Underground on its future as an arts institution. Mostly this has been confined to creating a curatorial agenda to use for fundraising, and tweaking the long-term spatial concept, but over the summer the National Building Museum gave us the opportunity to make something happen now. NBM donated the 750,000 balls from their Beach installation to the Dupont Underground, with the idea in mind that the balls would be repurposed for an international competition to design a site-specific installation within the DU. Dupont Underground would be responsible for moving the balls out of the Building Museum and into the Underground.

the ant-line started in the Building Museum...

...and ended in the tunnels under Dupont Circle.

With no budget, and limited staff, we called on our network of friends and supporters and enlisted what amounted to a massive ant-line of volunteers to pack the balls, move them across town, and into the DU. The numbers are thus: 750,000 3” balls packed in 1600 24x24x24” cardboard boxes. The effort was so large -and videogenic- that we attracted way more press coverage than we imagined. Local and national TV affiliates, NPR, the architecture press, and the dailies were all present as we packed up the Beach and hustled it across town. Remarkably, the boxes occupy a very small part of the overall Dupont Underground tunnel system. It is a bit evocative of this:

....the final scene of Raiders of the Lost Ark.

Now the fun begins. Archotus is now creating the competition that will repurpose the balls. The publicity boost Dupont Underground received from moving the Beach balls has given us a leg up on fundraising for the next phase. The competition should go live over the winter, with a spring goal for the installation and opening. Keep your eyes on this space!

Mirrors allow for far-away selfies...

Beached

Back in graduate school, a professor once claimed that one needn't visit any particular piece of architecture to know whether it was good architecture, the merits could be determined in images. Thankfully, there are an ever increasing number of “acts of architecture” that require visiting, and right now our favorite is Snarkitecture’s “Beach” installation at the National Building Museum.

“The Beach” is the National Building Museum’s latest effort to embrace an expanded notion of architecture. 2014 was Bjarne Ingels Group’s BIG Maze. Collectively, these two installations signal something akin to New York’s PS1 Courtyard installations and “Warm Up” parties starting to happen in Washington DC. Last night, in our capacity as programming consultant for Dupont Underground, Archotus partisans went down to The Beach to meet Snarkitecture, put our feet in the sand and ride the waves.

The Beach is 750,000 three-inch-in-diameter translucent plastic balls contained within a walled rectangular space with a bi-level white astroturf floor, sloped down in the middle to evoke a shore. A pier extends into the three-foot-deep sea of balls, and there is an island off shore you can swim to. A wall of mirrors at one end of the space multiplies the effect and simplifies selfies.

Grits? Creme of wheat?

The Beach does not look like much on paper. Early renders of the project were underwhelming, but in an intriguing way. There is a mode of practice in architecture right now that is deliberately reductive, stripped down and almost mute. Different practitioners have arrived here through different philosophies and approaches: SO-IL plays the social and theatrical, Philippe Rahm foregrounds the subject body, and Formless Finder plays contrarian with materials, to name a few. These practitioner’s work can be apprehended on paper, but there is a danger of misconstruing each piece. This work speaks softly and requires that you get up into its face. This work must be activated by people. And that requires a first hand visit.

Taken as a singular idea, a ball pit for adults sounds fun, but not particularly inventive. You can find out how to build one on Wikihow. But that is not what The Beach is. The Beach challenges some spatial and psycho-social assumptions.

Spatially, The Beach confounds scale. It playfully subverts the seriousness of the Building Museum’s massiveness. The central open space that was once the working floor of the nation’s military pension office rises up five levels, the roof held aloft by two colonnades of four massive columns. Add the Beach and the space becomes surreal. The columns are like redwoods, their scale is confusing, their faux marble finish is, strangely, also scaled beyond any earthly marble we’ve ever seen, and the balls at their feet start to be read as something else. Suddenly you are a tadpole in a plastic castle terrarium surrounded by your future siblings in egg form. The caviar-like quality of the balls only increases the farther away you get. If you are lucky enough to be able to pay a visit to the fourth floor catwalk, the installation becomes a platter of some strange tagine.

The surf was rough but people went in anyway.

On the night we visited, Snarkitecture was giving the keynote address to the AIAS (American Institute of Architecture Students) Grassroots Leadership Conference, the Building Museum was filled to the brim with future AIAs in business casual. Snarkitecture gave a quick run through of their projects, and then bid everyone to enjoy the Beach. Never have so many people ignored the architects and moved so quickly out of a lecture. In an instant, the Beach was filled with diving, floating, floundering future architects.

The social aspect of the Beach became clear: it is only complete when it is interacted with. The Beach requires activation, it cannot simply be viewed and contemplated. And, remarkably, interacting with the Beach can result in some of the same awkwardness one might feel at an actual beach. How much fun will I allow myself to have? Should I just watch? Or read a book? I’m feeling pale and un-athletic. Diving in is delightful, buoyancy is easily achievable, though swimming takes effort. The Beach is about as far removed from big “A” architecture as one can get. It is a simple idea, with complex effects. Those effects are surreal, both spatially and psycho-socially. They transport you, but they require you.

We’d like to thank the Building Museum for inviting us, and Snarkitecture for entertaining our currently-top-secret ideas for the future of the Beach balls.

Tiny houses, OMG!

We've been having a debate about tiny houses at Archotus. The tiny house phenomenon seems to have peaked in our collective conscious, as evidenced by this recent bit of snark. Here is a snippet of intra-office conversation about LILLU, who is currently a trailer with a dream:

C: I have some issues with the tiny house phenomenon. To me, it’s a little like Libertarianism: it hits all the right buzz words: freedom, autonomy, individualism, etc. But the promises are vacant because you still need society and its systems. With the tiny house in most places you still need the grid; you end up parked surreptitiously behind someone’s garage, and in some cases you are creating an environmental nuisance.

D: This is part of the reason I am trying to make LILLU combinable, I don’t want to hold it to some notion of autonomy, it should be a kit of parts, or like a family growing. It should be able to become part of the fabric of different densities of habitation.

C: But would you not agree that the tiny house movement is kind of another manifestation of American’s fetishization of a singular idea of home? Like we can’t get over the idea that we should be pioneers, taking over the wilderness in little autonomous units, a Little House on the Prairie impulse manifested in educated people who should know better.

D: Well, I think it is pretty established that people like to have access to outdoor space, preferably space they have some control over. A small house on a small plot of land is an ideal, and I don’t think it’s bad. It does limit density but, you know, we’ve all lived in different scales of cities and all cities have vast swaths of dense but low-rise neighborhoods that could be denser and healthier if the zoning allowed smaller lots. There are many different ways to live on this earth, and for the most part it should remain that way, and so should the impulse to improve upon all of them. The only way of living I take issue with, and am doing so through this project, is the absent one. Why do you decide to live the way you do? It’s a worthwhile question, and the answer “because that’s the way it’s done here” isn’t sufficient.

C: But wouldn’t we be better having tiny apartments in dense aggregations where we can share resources more efficiently? Think of a large aggregation of tiny houses: like all cute things, put too many in one place and they get scary.

D: The tiny house is not a replacement for the apartment, its a different thing entirely. In fact I think you could make the argument that the tiny house that is mobile could serve its inhabitants longer and better than an apartment, or a larger fixed house. LILLU can go places. If I made LILLU in grad school, I’d still have her and would have lived in her in at least three different locations.

C: All things turning out perfectly, perhaps. But isn’t part of our modern nomadism about experiencing new things and that includes different forms of housing, different types of neighbors, different views, things like that. If you are carting about the same shell, when you are home you might as well have never moved. In a way it is like the virtual house we live in on our computers. Same interface, different day. Do you want that as your actual house?

D: I disagree with the idea that you would not experience your new surroundings in an exciting way. I think of the habitant of a little house being more adventurous than that. Besides, the LILLU concept is perhaps in a different realm than the mini shotgun house on a trailer with the planter of flowers in front of its one sad window. LILLU is really a kit, ideally it could be reconfigured, different parts sold or traded, it could actually conform to code in certain conditions it could become just a small house. But still mobile.

Proportionality is really important here. One of the issues - and I think your term fetishization is appropriate - that I have with many tiny houses is how they use house typology clichés in unfortunate ways that don’t acknowledge the proportions we are dealing with. At the tiny scale a house is not efficient if it is a Monopoly house, a window is not a window, it is an aperture, a void, a portal. Doors, windows are the same thing. Even walls should not be limited to wallness, they should have the ability to open or shift.

H: I like the idea of thinking about proportionality in relation to time. What you are proposing here is a house that changes proportion over time. So proportionality becomes something that enters the fourth dimension. That’s kind of cool.

We want you to crash our party: Human Rights Campaign post-SCOTUS

Love won!

Several Archotus partisans were happily moving from one happy hour to the next this past Friday, June 26 - the day that the Supreme Court of the United States liberated marriage from heteronormity - when we passed the headquarters of the Human Rights Campaign. HRC is basically The League of Justice for all things LGBT, and a substantive party was going on in their lobby, while outside Equality flags were being handed out and pictures snapped.

There was rainbow cake and an open bar...

In Washington, legislative or legal victory parties are common, but open-door celebrations are not. HRC was having the biggest victory party of its life and there was no guest list, no bouncer, not even a security guard. In a town full of glassy lobbies that might wish to project the idea of accessibility and transparency, most are actually human terrariums designed to maintain distinct divisions: the in and the out, the invited and the uninvited. The night SCOTUS declared marriage equality, Human Rights Campaign was practicing what the architecture of their building preaches: openness and inclusion.

Note to self: rogue balloons can hi-jack your message.

Big "A" little "a", what begins with "A"?

The block quotes below provide a good explanation of what capital "A" Architecture means, and why we like to move freely between the minuscule and the majuscule, to the point where the difference becomes fuzzy....courtesy of Yvonne Gaudelius' essay "Kitchenless Houses and Homes, Charlotte Perkins Gilman and the Reform of Architectural Space"

..."there is a great deal of difference between Architecture with a capital "A" and architecture with a small "a". Big "A" Architecture is Art (also with a capital "A"), whose existence and health rely upon a profession that cannot afford to have itself associated with the blue-collar activity of building. Architectural critic Diane Ghirado points out in her introduction to Out of Site: A Social Criticism of Architecture that “there is a tacit and often explicit professional agreement that nonarchitect-designed buildings cannot be considered Architecture”. That big "A" Architecture is kept separate from little "a" architecture is a matter of professional survival for architects.

Little "a" architecture, however, comprises approximately 80 percent of structures that are built in the United States. Just as literary canons are formed around the exclusion of, for example, the works of women writers, so too architectural canons are established. Not only do these canons exclude small "a" forms of architecture, but they also serve to keep in place the relationship between architecture and ideologies such as gender. Through the virtue of the power of art, big "A" architecture legitimates what is built. A feminist analysis of architecture, by placing gender at the center of inquiry, necessitates a dialogue that unveils this paradigm. We need to move away from typical formal dialogue that establishes dualisms and dichotomies within architecture - for example the distinctions between big "A" and little "a" architecture, public and private domains, interiors and exteriors, form and decoration, which are conditions in which one term, by necessity , becomes subordinate to the other."

From: Charlotte Perkins Gilman, Optimistic Reformer, Jill Rudd and Val Gough, editors. University of Iowa Press, 1999

BLACK, GLASS, INFORMATION

Sometimes, in the space between one language and another, a misapprehension can become art. We see this in one culture’s affinity for another culture’s dross. The cliché of this phenomenon might be ham-handed American comedian Jerry Lewis –loved by the French; or the banality of Japan’s Hello Kitty - loved by Americans. While working at Studio Twenty Seven Architecture, Archotus was asked to create way-finding signage for Gallaudet University that would operate between American Sign Language and the written word. The hope was that we might come up with a new form of signage, a kind of frozen ASL. And, in the spirit of Jerry Lewis and Hello Kitty, the fact that we didn’t know American Sign Language could be a potential asset.

The context and content were straightforward. We were redesigning the public spaces of the University’s residence halls, and inside the main entrance of each hall there was an Information Desk and Wall. The Desk was the domain of a student greeter-cum-factotum. Close to The Desk was The Wall, a floor to ceiling tack-able surface where posters and notices could be placed.

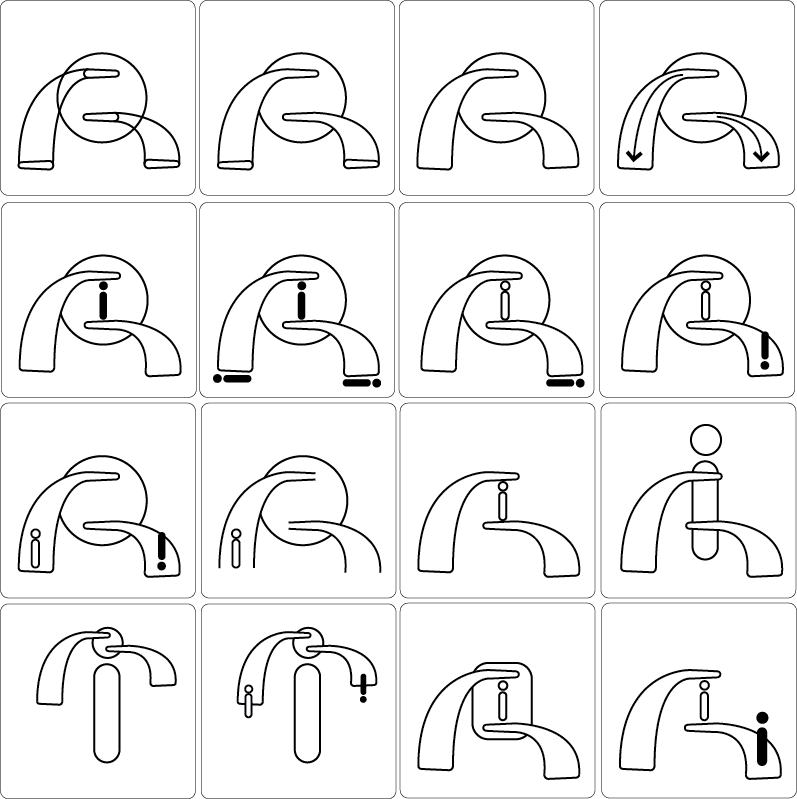

The initial design called for “Information” to be spelled out in a six-inch sans-serif font, somewhere in close proximity to The Desk and The Wall. The client asked if we could integrate artwork into the sign, using the gestures of sign language to say “Information”, without spelling it with actual letters, and without pictograms of ASL “finger spelling”. Ideally this new “sign” would be both the signified, and the signifier, to go back to Semiotics 101.

In struggling with this abstraction, previously unintelligible relationships were revealed to us. The act of signing appears gestural to those who hear with their ears and speak with their mouths. But to those who speak with their hands and hear with their eyes, the hands are the mouth – the primary transmitter of meaning, the unelaborated information – and the face is the hands – the site of the gesture, the emphasis, the sub-text. The relationship a hearing person expects is, in fact, inverted; and this inversion is the cause of misapprehension. Those that hear with their ears read the expressions of emphasis in a hand-speaker’s face as pronouncements of emotion that seem exaggerated and baroque.

Above: Former NYC Mayor Michael Bloomberg's ASL translator Lydia Callis, added the emotion to Hizzoner's press conferences.

A similar lack of understanding happens at the hands. This is where our attempt to create a new form of visual signage was going all wrong. We were attempting to pull hand movements out of time, scrub off the “z” dimension, and place them on a two dimensional surface. What evolved was a series of lines that carried no meaning as they were removed from their frame. We were trying to document what we thought was a simple gesture, but by removing the movement itself and the reference back to the human body, we dissolved its meaning.

We use gestures to convey information, sometimes consciously, sometimes unconsciously. Gestures are active ancillaries of both communication and thinking, regardless of whether one speaks with the mouth, the hands, or otherwise. Linguists assign a kind of sub-narrative to gestures, in which a gesture not only emphasizes the words being spoken, but also conveys unspoken thoughts, both about the subject of the statement, and the identity or state of mind of the speaker and the interlocutor.

As architects we are taught many ways to visually represent ideas; and sketching is the most basic visual medium for most. Given the hierarchy of work in a typical architecture firm, and the rushed time of client meetings, sketching is often the most common way an executive level architect will convey a project. Sketching feels gestural, indeed, the intent is to capture a physical essence of a spoken idea; to use the fewest lines in the shorted period of time to convey the most amount of information. It is communication through the movement of a hand tracking in space.

In this respect sketching is analogous to signing as a form of communication. In a project meeting one day, we were discussing color. In ASL, the sign for the color black is a horizontal sweep of the forefinger across the forehead. To the mouth-speakers present, the sign seemed highly gestural, and none of the implications one might assume from such a gesture have anything to do with the color black. Drowning? Lobotomy? Sweating, perhaps? Wearing a hat? There, we were on to something. The Gallaudet team explained that the sign was derived from laborers who, after hours of working, when they removed their hats they would have a black line across their foreheads. The one-fingered slide across the forehead indicated this line of black.

In signing, the body and the space in front of it become the medium on which an image is produced. That image is a signifier for an abstraction that becomes, to some degree or another, removed from the sign. Yet signifier and signified can be universally understood in the same manner that converging lines on a page can resolve as perspective, once the logic is known. In the case of black, the logic of the sign is a kind of narrative. The narrative confirms the sign, and then falls away, the sign is forever after an understood abstraction.

Another hand sign we learned quickly was the signifier for glass. As if to prove the many ways in which signs relate to experience, the sign for glass is almost a one to one relationship. Tap your front teeth with your fingernail. That’s glass. A haptic, material quality, it is a sign without narrative. For a hand-speaker it is the equivalent of onomatopoeia. Yet, again, this is a sign that, taken as a gesture, would be confusing to a mouth-speaker. Tapping the teeth with a fingernail is more an expression of mental state, implying a state of thoughtfulness, or intent listening. Or a subtle way of indicating that a friend has food stuck between her teeth.

The sign for Information is straightforward. One hand starts at the head and extends forward to the interlocutor at the same time as the other hand starts at the mouth and extends forward. Both hands start with fingers pursed –tips touching; they then open up as they go through the motion, as if offering something. It is a bit like blowing a kiss, and with it, a thought.

copyright Kaori Takeuchi

Gallaudet had put the Information Wall art idea to Kaori Takeuchi, an artist and Gallaudet graduate known for Manga-inspired work. Her concept was a version of the kind of drawings you see in text books on sign language: photo-realistic figures creating the signs, with movement waves following the travel of the hands. There were two sets of hands, “start” hands and “finish” hands. While this approach made sense, and provided us with a starting point, it did not feel abstract enough to become something other than a text book illustration.

We took Takeuchi’s images though a distillation process, trying to find the minimum information in “Information”. What holds more meaning, the hands or the face, or their relationship? We started with both, with the idea that you could have a kind of alphabet, an array of fixed units that described the sign: minimized face with eyes and mouth, hands with digits and a larger thumb. The face implies the level of the hands relative to the body. Perhaps, with sweeping movement lines, you could abstract any sign from these?

We soon found out that this did not work well. The face was too face-y, the fingers weren’t doing anything for us, and other accidental meanings were starting to impose themselves. Our proto-alphabet, while generic, was not dynamic. The more elements we got rid of the clearer the idea became.

The face became a circle, the hands, merged into the movement, and we began to have a pictogram that made sense, if one knew the ASL sign for information. To situate our pictogram between ASL and written language, we replaced the face with a lower case “i”. Our new pictogram iterations had moved into the space between ASL and written language.

Our creation, we realized, was an unsophisticated version of Asian associative and pictographic-phonic characters.[6] Pictographic characters are, at their root, sketched gestures that depict an object or idea. They are referential and convey meaning though a visual association that is buried in culture and symbolism. Associative characters depict relational concepts between a series of two or more pictographic elements. The meaning is inferred in the relationship of the elements.

To create a two dimensional gesture sketch based on a hand-signed language, each element is necessarily associative: the hands, the movement, the body, must be implied even if one or more falls away. It is two levels removed: the sign is derived from an abstraction, and our abstraction is then derived from the sign.

Unfortunately, we were never able to put our experiment into production. The dormitory renovations ran into the new academic year, and the Gallaudet project team found more important things to spend their time and money on. We were left only with new knowledge, and an experience that we hope will inform other projects down the road.

POST-MAX METROPOLIS

This article originally appeared in the book The SANAA Studios 2006-2008, Learning From Japan: Single Story Urbanism, Florian Idenburg editor, Princeton University and Lars Muller Publisher, 2009. A brief review in Metropolis can be found here.

Genchiku is a Japanese neologism meaning, roughly, “reductive construction.” It belongs to the same realm of paradox wherein lies the bigness of shrinking Japan, and the culture of newness hiding the nation’s aging population. And genchiku puns nicely with the word for architecture, kenchiku.

Architect Hidetoshi Ohno explains genchiku in the catalog for the 2000 exhibition Towards Totalscape: “Until now building more has meant increasing value. But we are starting to see that building less can increase value too.” [1] Increasing value while decreasing production necessitates creating new polyvalence and hybridizing old use, strategies that are being deployed in the architecture and urban policy of aging, depopulating Japan. If one thinks of the Japanese economic engine of the 1950s through 1980s as a producer of rampant, predominantly characterless, market driven, kenchiku - in a nation where 20%twenty percent of GDP comes from the construction industry - then in the post-bubble, post-max age, genchiku is an appropriate new mode for the built environment.

In 2005, Japan became the first large industrialized nation to experience population decline attributable entirely to natural causes; more people are dying in Japan than are being born, without the presence of war, epidemic, or migration. By all recent projections, depopulation will be the default condition in most of the developed world by the next quarter-century, but Japan has reached this watershed before any other nation. Depopulation on this scale is accompanied by societal aging as the conventional population pyramid is turned on its head. How Japan responds to aging and downsizing will serve as a bellwether for industrialized nations, and implications for the built environment are vast.

Through the economic crash that precipitated the 1990’s “lost generation,” Japan’s great megalopolises, have remained stable or increased in density, while many smaller cities – particularly those dependent on disappearing industries, began to fade away. Municipalities caught in the middle, the peripheral “bed towns,”, newly minted suburbs, and mid-sized semi-agricultural agglomerations, were also condemned to shrink and possibly disappear entirely.

In the wave of introspection that followed the bubble, the government reappraised the laisser-faire, top-down national “consensus” that powered Japan through the latter half of the twentieth 20th century; now a locally-driven neo-liberal model has emerged. Individual regions, cities, and municipalities have been set in competition with each other. The result is emerging genchiku urbanism, as agglomerations of all sizes are assessed by new standards of viability, amenity, and convenience that encourage both scaling back and up-scaling.

On a regional scale genchiku can be seen in trends of consolidation, as municipalities with high debt, shrinking populations, and poor tax bases merge with more robust neighbors. From 2005 to 2007 the number of autonomous cities, towns, and villages in Japan shrunk from 2190 to 1,822. [2] In a country whose citizens tend to be emotionally invested in local social support systems, consolidation has had profound effects on the collective psyche. In towns that have nominally disappeared, communities have lost their identity.

Locally, genchiku can be the result of the push to hone the identity of a city or town, making it more attractive by developing its culture while downplaying and reworking its voids. In the most ambivalent communities this might result in something as banal as a newly conceived town motto, while the more successful cases create new value through core redesign, investment in attractor enterprises, and cultural projects.

Finally, on the scale of the street genchiku can take on another meaning, implying a form of gentrification as wealthier households merge multiple units to form larger homes. Still, this type of gentrification is a break from past practices, when developers sensing a market shift would destroy perfectly good housing to respond to the new demand. “For a hundred years, we’ve played at architecture as a kind of expensive hobby, tearing down and rebuilding buildings sometimes before they were paid for,.” Ohno writes, “But this becomes less and less feasible as the population ages. Now a quarter of the population is over 65 and another quarter is constituted by minors. A society where one half the population supports the other half is much less productive...When you don’t have the extra resources any more buildings stick around longer.” Rehabilitating the old, in a society where youth and newness is virtually a religion, is a project indeed.

Ageing Up, Not Out

"It seems possible that a society in which the proportion of young people is diminishing will become dangerously unprogressive, falling behind other communities not only in technical efficiency and economic welfare, but in intellectual and artistic achievement as well." - 1949 Report of the Royal Commission on Population, United Kingdom

The Japanese economic miracle of the late 20th twentieth century was driven in part by artificial demographic manipulation in the pre-war and immediate post-war years. Going into World War II Japan was newly industrialized, virile, beholden to Nationalism, and questing for an empire. A population boom ensued, encouraged by government sloganeering: “let’s give birth, let’s increase!”. [3] While WWII leveled Japan’s industrial complex, the children of the pre-war boom lived on, creating a short-term overabundant population of dependants in a society that had just lost many of its most productive members. In 1948-49, the government launched an initiative to suppress Japan’s birth rate, cutting Japan’s post-warpostwar “baby-boom” to the four years between 1945 and 1949. The result was a population “trough” in the late ‘40s and ‘50s that, in following the earlier pre-warprewar peak, created a wave that would reverberate into the coming decades. [4]

In 2008, the crest of that wave is a population of healthy, long-lived citizens over sixty. Japan’s surge in life expectancy was a product of rapid economic growth that created rising incomes, healthier lifestyles and diets, and improvements in medical care. But the demographic tilt created by a healthy, aged, boom population has resulted in a steady decrease in the overall working-age population. As the “company men” of the bubble economy take their retirement, and live well beyond their projected life spans, Japan’s shrinking workforce must support an ever-increasing number of aged dependants.

Decades of laissez-faire government have fostered a robust tradition of local self-reliance in the typical Japanese municipality. Citizen membership in local organizations is nearly universal, and it is at this level that we see many of the more successful responses to the shrinking, ageing society. Identifying and capitalizing upon a municipality’s unique characteristics and turning those into a “brand” is now a strategy at the most local level. The town of Kamikatsu is a successful example. Located in Tokushima Prefecture on the island of Shikoku in south-west Japan; half the 2,200 residents are above the age of 65sixty-five. Yet local initiatives are remarkably cosmopolitan and innovative.

Embracing the latest in green technologies, Kamikatsu has put itself on the map in its quest to become Japan’s first “zero waste” town. Currently household waste is separated into thirty-four different categories to be recycled. That penchant for sorting is equally important to Kamikatsu’s leaf-and-flower-picking cooperative which supplies Japan’s garnish trade. The cooperative is staffed by 177 members of whom the average age is 70seventy. The business is Iinternet-based, and those same elderly operate both the front and back ends of the business, logging-in to take orders each day. [5]

The success of these initiatives help dispel the notion that the elderly cannot adapt or contribute meaningfully to the current economy, neither would these initiatives have been possible without robust local organization and the participation of a sizable number of Kamikatsu’s citizenry. This is a human resource form of genchiku: maximizing the usefulness of existing resources, and hybridizing uses. To increase the productivity of all working-age citizens, and extend that working-age to a level more appropriate for contemporary life -spans, requires rethinking dominant social assumptions.

Sociologist Chikako Usui proposes a blurred, irregular form of life-cycle that contrasts sharply with the former, Fordist model: “In the post-Fordist economy,” she writes, “workers will be more differentiated in terms of their skills, sequential careers, mixing of part- and fulltime work, and gradual retirement (as opposed to complete, one-step retirement). The traditional male career patterns will be “feminized,” with more chaotic career transitions throughout life. A life cycle in which adulthood is supported by a stable employment and old age begins with retirement will be replaced with intermittent employment, continuous educational training, and gradual retirement.” [6]

Building Down, Not Out

In 2003, the municipality of Onishi commissioned a new community center. Onishi is at the high water mark of the Tokyo Metropolitan Area’s expansion, just under an hour from the city center by high-speed train. As Tokyo retracted through the 1990s, Onishi became a shrinking tidal pool, one of many depopulating bedroom communities searching for its own identity and striving to remain attractive and vital. Onishi was merging with a neighboring municipality and its citizens feared an outright erasure of identity. The community center was a strategy to coalesce the local population and give Onishi a larger, global identity.

The resulting project, executed by SANAA, succeeds as both a branding exercise and a polyvalent local resource. The Onishi community center fights the condition of suburban dispersal by creating a magnet of activity in the center of a dying town. SANAA achieved this through their form of hyper-minimal, aestheticized “reductive construction” where transparent spaces frame both exterior and interior activity in a manner that unifies the site and its context. SANAA’s high profile in a nation that exalts material culture took care of the branding.

Taking the concept of genchiku as a multi-disciplinary way-finder, the Onishi community center stands out not as a reconstitution or recyclage but as a social concentrator. The best-case scenario for towns like Onishi is that such projects become magnets of value and amenity, strengthening local bonds and attracting continued interest in the town. But in the post-max, depopulating world, every successful Onishi, helps speed the creation of neighboring voids. Laila Seewang’s Onishi alternative – created in the SANAA studio at Princeton - accepts the inevitability of depopulation, anticipating and reconstituting the voids while recycling the abandoned excess.

Seewang’s proposal unfolds over thirty years. She describes it as a “reverse” architecture that “actively dismantles the unused fabric of the town.”. Seewang imagines a ribbon of “collection walls” that serve as both storage facilities for the recycled detritus of dismantled buildings and as “memento” niches for displaying the active memory of a town in slow disintegration. The project provides a collective emotional outlet for a situation in which there is no catharsis, the niches and their content are a substitute. At the same time the ribbon walls create a civic unity much in the same way SANAA’a transparent community center does, lending an infrastructure for constituent functions, the difference being that Seewang’s Onishi is programmed to become a beautiful ruin.

The city of Towada is another municipality negotiating its decline through genchiku. Situated well outside the urban agglomerations that belt Japan’s main island, Towada is four hours north of Tokyo by high-speed train. The city has suffered all the symptoms of an agricultural business center disappearing in the new economy. Too remote to be attractive to young professionals, Towada loses its youth to the larger cities, leaving a predominantly elderly population. In 2005, Towada merged with neighboring Towadako. Pooling their resources, the new entity created a cultural organization, “Arts Towada,” designed to reenergize Towada’s lifeless central business district.

From an initial project to fill empty lots and storefronts with an annual arts festival, Arts Towada has developed into a unique model for cultural “infrastructure.” Using a “dispersed gathering of white boxes” scaled and distributed in such a way as to encourage exploration and elaborate on the existing business district, Ryue Nishizawa has created a culture activator in a dying town. Each “box” is conceived of as a “house for art”, the scale of the volumes and the voids between merge with the exterior context. The art faces both in and out, and occupies interior and exterior, breaking out of the gallery spaces. The terrain of the project is as open as the central street itself, taking on the character of both a park and a street, a hybrid infrastructure that reorients the center of town.

While Arts Towada is built in an updated, minimal, modernist mode, the site plan, its rationale and its intentions are far from the Functionalist preoccupations of traditional Modernism. The organization is designed to attract local youth as well as place Towada on the global arts stage. The spaces are multi-purpose, serving as workshops, community meeting rooms, and activity centers. Florian Idenburg calls it a “settler camp,” merging the “global and local, cultural and civic” and posits, “when the rest of Towada has shrunk until all but the Art Center has gone, a beautiful little village will remain.” [7]

Japan’s dominant cities are in no danger of becoming “little villages” — whether beautiful or post-apocalyptic — any time soon. While population projections indicate substantial decreases as the century progresses the effect will by no means deurbanize Japan. The next generation will likely see consolidation as a by-product of the current dispersial. According to conservative estimates, by 2050 Japan’s population will be close to 100 million, dropping 17%seventeen percent in fifty years; less conservative estimates predict a fall to 80 million. [8]

Market analysts have long been predicting that the Japanese population vacuum would precipitate an international financial crisis. In 2002, Ken Courtis, then vice-chairman of Goldman Sachs, claimed that Japan would soon create the “largest economic crisis since the 1930s.” [9] However, recent events have proved that over-heated, as opposed to under-heated markets are a far larger threat, a lesson that could have been learned from Japan’s 1989 bubble-burst, which was in many ways a preview of the current worldwide economic crisis.

Likewise, dire warnings of the end of Japanese society as we know it are greatly exaggerated. In a nation famous for small cars and even smaller hotel rooms, whose citizens are adapted to very little elbowroom, the future can be considered healthy. Many Japanese who were priced out of cities and forced to endure long commutes from the suburbs are moving back towards the center as prices continue to fall, and the voids left behind as populations shift could be considered an opportunity to reclaim green space and regenerate an environment long lost to development. Indeed, seeing these trends as an opportunity and not a catastrophe will spell the difference between successful and unsuccessful policies.

To date the best initiatives have been activated at the local level, but networked globally. Architect Morika Kiro optimistically regards past transformations as the key to the future; suggesting that in the historical context of a nation that has twice recreated itself in the previous century, “...it is only natural that even today the Japanese both consciously and unconsciously believe that they have a choice to initiate political, social, and cultural transformations vast in scale.” [10] How Japanese society as a whole chooses to adapt will have intriguing implications at the global scale, as other nations begin to wrestle with these same problems. Architectural precedent in the form of genshiku’s “reductive construction,”, propagated by SANAA and like-minded practitioners, may be Japan’s next big export.

[1] Caroline Bos and Ben Van Berkel editors. Japan Towards Totalscape: Contemporary Japanese Architecture, Urban Design and Landscape. NAi Publishers, Amsterdam NL, 2001

[2] Consulate General of Japan, San Francisco. Consolidation of Local Governments in Japan and the Effects on Sister City Relationships, January 2006.

[3] Chapple, Julien. “The Dilemma Posed by Japan's Population Decline”, Electronic Journal of Contemporary Japanese Studies, 2004.

[4] Matsutani, Akihiko. Shrinking Population Economics, Lessons from Japan. International House of Japan, Tokyo, 2006.

[5] McCurry, Justin. “Climate change: How quest for zero waste community means sorting the rubbish 34 ways.” The Guardian UK, August 5, 2008.

[6] “The Demographic Dilemma: Japan’s Aging Society.” ed. Amy McCreedy. Asia Program Special Report. Woodrow Wilson International Center for Scholars, January, 2003.

[7] Florian Idenburg, “The Culture of Decongestion.”, Domus #915, January 2008

[8] Fujii, Yasuyuki. City Shrinkage Issues in Japan. Fuji Research Institute Corporation / Urban and Rural Issues. Mizuho Information and Research Institute, 2008.

[9] Fulford, B. “The Panic Spreads.” Forbes, Feb 18 2002.

[10] Bos, van Berkel